Unwanted: The Legacy of Soviet Cemeteries and Monuments in Central Europe

The Iron Curtain Fell over thirty years ago, but the painful remains of those years of oppression are hard to deal with.

I’ve visited most of the Warsaw Pact countries, and with the exception of Bulgaria, visited Soviet cemeteries in each of them. Some are better tended than others, but what they all hold in common is that they are often the last vestiges of Soviet oppression that began without the consent of the occupied countries after World War Two. What I find interesting as a foreign guest is the varying degrees of upkeep, the monuments themselves, and most interestingly - the signs of visitation by family members.

I am a lifelong cemetery visitor. It all began when I was a boy, when visiting family cemeteries was a typical activity on our visits to Alabama, where my mother comes from. There are cemeteries where I’m related to everyone resting under the soil, and it’s an interesting feeling. I feel connected, but from a distance. Cemeteries are fascinating to me. The monument designs, dates, and even the namesI find interesting. Whenever I go somewhere new, I usually take in a cemetery or two, and this was how I caught onto the controversy of Soviet burials in the former Warsaw Pact countries.

Hungary

Hungarians have had it rough since the First World War. They lost ⅔ of their territory, and I’m not talking about Austria-Hungary, I’m talking about Hungary proper losing all that territory. Most of it belongs to Romania now. The Second World War was tough as well, where they initially sided with the Third Reich, but in 1944, they tried to switch sides, which triggered a full German invasion. In came the Red Army, who were happy to take on the role of oppressor. Hungarians in general did not want to become a communist country, and in 1956, there was an national uprising, which led to an invasion by Soviet troops, accompanied by units from other Warsaw Pact countries. It was a bloody conflict, and is a sore spot to this day.

The Ferihegy cemetery on the east side of town, by District VIII, contains a Soviet section with soldiers killed in World War 2 and the 1956 uprising. Nearby is a section dedicated to Hungarian Communists who were killed helping the Soviets.

The Soviet section also contains Soviet citizens who died in Budapest throughout the Cold War for a variety of reasons. They are further south nearer the footpath by the south wall. Several women, such as nurses and clerks are buried there.

Despite strong negative sentiments towards those buried here, I found this section better tended than many other sections of the cemetery. Everything was clean, the grass wasn’t out of control, and there were signs of visitation, such as candles, on some of the graves. Like most Soviet cemeteries I’ve seen, there is a combination of mass and individual burials.

The circular section containing the graves of Hungarian communists who died fighting their countrymen in 1956 is the most controversial. Fighting brother against brother is never easy to deal with, especially since this happened in living memory. I tried to find out what was originally on the sarcophagus, as it appears that there was something there that was chipped off, but the people I asked were understandably upset, and did not understand why I was curious.

The current leader Viktor Orban’s chummy relationship with Moscow is seen as a betrayal by many Hungarians, who know friends and family who were persecuted by the communist puppet regime that collapsed only a few decades ago. His pro-Hungary stance rings hollow in this regard - how could he be a champion for his people when he licks the bloody boots of their former oppressor?

Slovakia / Czechosovakia

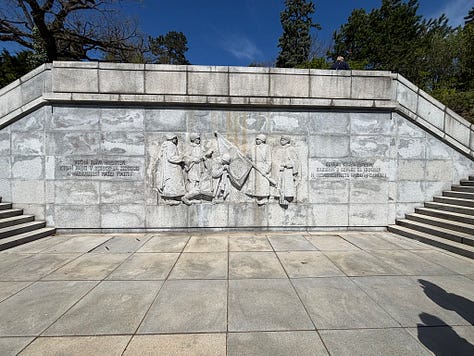

Commanding the beautiful city of Bratislava from a hilltop stands a magnificent Soviet monument surrounded by a combination of mass and individual burials. I found several Heroes of the Soviet Union buried here. Up until recently, this was part of the greater Czechoslovakia, who like Hungary, had the terrible experience of not only occupation and terror by the Third Reich, but also by the new communist government overseen by the Soviet Union. 1968 was an ugly time for the country, when there was an uprising, followed by a major clamp down by the government. You won’t see many Soviet monuments left standing here, with the exception of this cemetery, called Slavín. I took a bus up the winding hill to see it. This cemetery was in fantastic condition, and is a popular place to visit by tourists, locals on a stroll, and family members decorating graves.

I really liked this cemetery. The quality of the monuments was stellar. I especially liked the photographs on the Hero tombstones. Senior Sergeant Gusko, 21 years old, is pictured wearing a Cossack hat. I wonder if he served in a Cossack regiment? Lieutenant Colonel (literal translation would be sub-colonel) Selishchev was 41.

The iconography of the bronze statues is beautiful and typical of Soviet monuments. Fresh wreaths and candles were by the central obelisk, and the grass and grounds were well-kept.

Aside from this monument, you won’t see busts of Lenin or Stalin while you walk around Bratislava, or any Slovakian city. Nowadays, Immortal Regiment marches attract counter-protesters. Regardless of politics, I think Immortal Regiment marches are still worth allowing - it’s how many people commemorate the sacrifices of the Soviet troops who broke the back of the Third Reich. It shouldn’t be pro or anti Russia politics that surround the Regiment, but whether or not you stand for the fall of Nazi Germany. If you want to scream and shout at family members carrying pictures of their ancestors who died for your freedom, just slip that red armband on and show us who you are. May 9th is for all of us, not just Russia. If the Regiment was de-stigmatized, that would take a lot of the cultural power away from Russia, who use World War 2 as the basis for all kinds of nonsense.

Poland

Poland is another country that was denied the right to self-determination after World War Two. The border between Poland and Germany changed, so Silesia became part of the new communist Poland. Ethnic Germans were expelled, with any trace of them washed, painted, or bulldozed away. While the Soviets wanted to be seen as liberators, Poles saw things for what they were - another age of bondage, just under a new master.

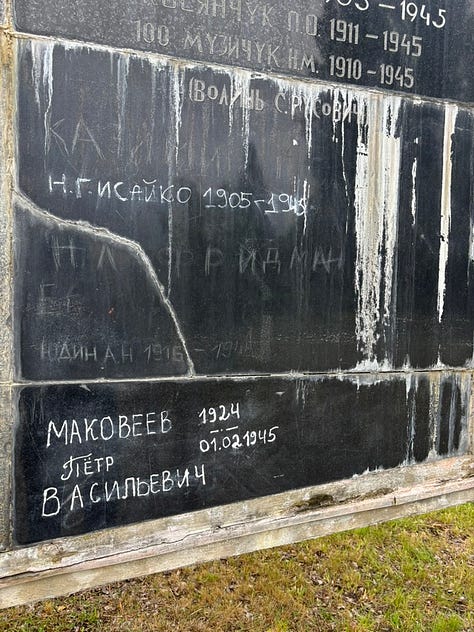

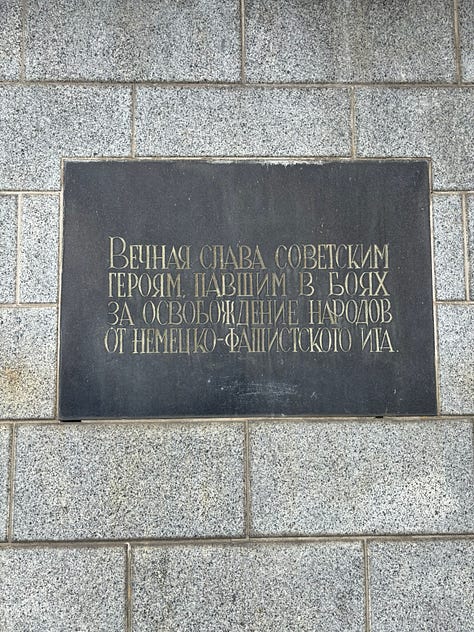

Soviet monuments have been removed since democratic Poland emerged from behind the Iron Curtain in the 90’s. The current law forbids public expression of symbols of tyranny, essentially to stave off Nazi and Soviet sympathizers. The only Soviet monuments that remain now are within cemeteries, which fall under different laws, as well as treaties with Russia, for the dead aren’t Polish, but from the vast reaches of the former Soviet Union. The upkeep of these cemeteries is the responsibility of the Polish government, and it’s obvious from what I’ve seen that they do the bare minimum. Like in Hungary and Slovakia, descendants and family members visit these graves, and it’s common to see the remains of candles and flowers at individual graves as well as collective cenotaphs.

There was a time when there were more Soviet cemeteries in Wrocław, but they were disinterred and reburied in these two collective cemeteries. There is apparently a final Soviet monument further south near the outskirts, and I will visit that to see if it’s still there.

The Katyn Massacre Memorial is located in a popular park due east of the old city, near the National Gallery. It’s a haunting monument. The angel of death’s face is incredibly sinister, but the darkness of the face under the hood and the sunlight made it hard to pick up on the camera. Sadly the Katyn Massacre was one of many instances of brutality visited upon the Polish people by the Soviets.

War graves are controversial the world over.

How do you think Black people feel walking past a Confederate cemetery? Or Germans visiting Poland, seeing these Soviet graves? There is an Austro-Hungarian Cemetery in Belgrade. It’s inaccessible to the public, visible only through iron bars. These sites tug at places that dwell deep within, because we all know someone connected to them. Wars are the subject of family stories, perennial enmities, and everlasting mistrust. How should we treat the cemeteries of soldiers from opposing forces? I think we should rise above and do the noble thing by keeping them up, with their symbolism intact. Erasure is a petty, awful thing. It’s what tyrants do, grinding names off of stones and pulling down statues.

Soldiers are people, and oftentimes don’t have a choice in what side they end up on. Just ask a Vietnam vet who was drafted how excited he was to be sent over there. Soldiers fight for their side, and they try their best - not for the sake of the politicians who started the conflict, but for their own skin and the lives of the men to their right and left. The days of mutual respect between armies has disappeared since the end of World War 1. Manfred von Richtofen, the Red Baron, was initially laid to rest with full military honors by Australian soldiers. I don’t think we’ll see Ukraine burying Russian war dead with any level of respect, and vice versa.

Regardless of politics, I think it’s worth seeing these places. They provide the basis for a holistic understanding of the conflict, and its aftermath. As a historian, I seek to understand the situation as a whole. The war’s over, I can explore as I please without crossing lines - I don’t take sides, I evaluate them.

Thank you again for reading, stay tuned for some video content!

-FT

Fascinating! Thank you for this interesting look at the current state of these cemeteries. I think that so many people can't get past the politics to see that regardless of what side these people fought on, they were still someone's parent, child, sibling, etc.

You’ve captured these really well, both images and also the spirit of the places